Throughout the process of working on my inquiry project, I have a daily struggle with how to characterize this journey I am taking with my students. I’ve referred to the project using the descriptors: play, project based learning, and inquiry. While preparing for this entry, I coined a new term, Interest Driven Learning, only to find I’d stolen it from many other sources far more intelligent than I. From a teacher perspective, this is certainly a constructivist endeavor. Most of the readings I’ve done on PBL have included examples of projects larger in scope and which required more research than our little project. I do feel that our game-making unit is a great learning laboratory from which to leap into a truer form of PBL in the future, but for now we’ll characterize it as Interest Driven Learning.

It’s funny. Weeks ago, as my team and I created the inquiry questions that would help lead us into this unit of study, the questions seemed to be directed at us, the teachers. Now that our students have begun their work, it seems that the questions apply to them, not the “educators.”

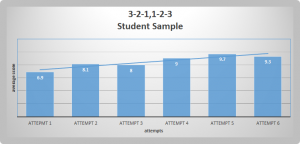

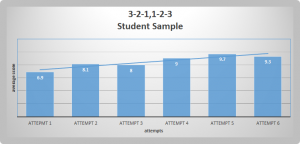

In my class, we finished up the teacher modeling process by creating Excel graphs of individual performance over six “play” sessions. Student graphs included “trend” lines so it would easily show whether they generally improved over the six sessions. After modeling, students were able to work independently to create the graphs. Based on the information provided, I was able to create a “seeding” chart, much like the NCAA March Madness basketball field of 64 teams. As PSSA testing began, we were able to use “down time” after testing as a space to play “best of five” series based on the seedings, and eventually crown a class champion. This became a popular spectator event as nearly every child wanted to witness 3-2-1 history!

Throughout the experience, students have been blogging about the game and blogging about ways to persuade teachers to allow their students to play. These seed ideas are now being used by students to write persuasive essays.

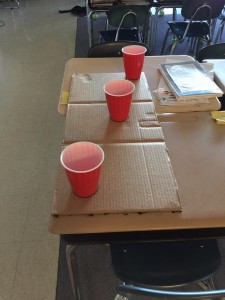

Next . . . to begin the next phase of our journey. The first question of our inquiry projects was: How can teachers create a meaningful unit based on play? The first answer was now clear. Model the process of taking an idea through to a more refined finished product. The initial game idea presented to students was bouncing a ball into a cup. The teachers allowed student experimentation and acquired feedback. It was determined that average scores were low, so we added ways to facilitate improvement including backboards, practice, and peer feedback on technique. The result was higher average scores and high student interest and engagement, related to collaboration, social skills, and math computation and analysis. Additionally, students saw that some decisions, regarding performance and changes to the game, were informed by data.

From the first inquiry question, the word “meaningful” strikes me on two levels. Anecdotal evidence shows a very high level of student interest and engagement, both in playing and math use. Additionally, students immediately expressed an interest in being able to create their own games, even after discovering they would have to incorporate math and writing. All indications are that what we were doing, and about to do, was meaningful to students and created a feeling of shared purpose.

How can we support the students and facilitate continual improvement? The teachers on my team agreed that in the next phase the work should be done by small groups, not individuals. Our first consideration was how to organize students. We wanted to do better than just randomly assign groups. Keeping in mind Adam Gates’s idea that brainstorming should first be done individually, we asked students to submit diagrams showing and describing their ideas for arcade style games. Identifying similar characteristics, we created groups of roughly four students. In my class, several students created basketball type games, field goal type games, as well as bowling, skeeball, and a maze-like game. Based on these diagrams, groups were assembled based on common characteristics. I asked the students to meet their partners, share their original ideas, and identify similarities that would help them see why they were grouped together. I was initially nervous about this, but they seemed to be able to generally find common ground from which to proceed.

How can we incorporate the use of fourth grade principles of math? As we wrapped up the teacher-modeling phase, I asked the class to brainstorm all of the math that was used with 3-2-1. They were easily able to identify statistical landmarks, measurement, and geometry, including the fact that I’d chosen cylinders to receive the ping pong balls. As students began to collaborate on their game, they included thinking about scoring and making to incorporate mathematical concepts, much like their teacher had.

How can we support the students and facilitate continual improvement?/How can we provide formative feedback? Before beginning phase two, I was concerned about how much to formalize this portion of the project. I thought about creating rubrics and session-guiding objectives, because this is how I’ve been trained. Not knowing how things would proceed, I decided that the only thing I wanted to have some control or influence over would be how they worked with one another. Working together is not a new concept in my class, and I trusted that this would work well, but I wanted to be sure to encourage a high level of on-task, respectful behavior, so, as a starting point, I wanted to create a basic rubric, mostly as a reminder. We now begin each working session with a review of this basic rubric to guide their interactions. As they gain more experience working with each other in the present context, I plan to have them create their own “collaboration rubric.”

As students entered the prototype stage of development, I walked around the room, checking in with groups, answering questions, and sharing ideas. As facilitator, my goals are to have a presence, make sure I understand the status of each group’s progress, keep their work moving forward, and give support when challenges arrive. One example of this is the group that is creating a hand-held maze type game, which I discovered from their diagram model. I wondered if they had considered how to erect the walls out of cardboard. I demonstrated some ideas for how this could be accomplished. From their reaction, I don’t believe they realized the challenge they had created for themselves, and I was able to identify and facilitate progress by showing them some ways to approach.

How can we measure success? As we consider this question, I acknowledge two perspectives, that of student and educator. Looking through the lens of “student driven,” we will ask students to consider what it means to be successful in this endeavor. Doing this will give teachers guidance and information that will help us plan and evaluate in the future, allow students to be reflective and consider how they’ve grown, enable students to explain the math they used to create and play their games, and provide an opportunity for them to write. From an educator point of view, we will consider all of the above and ask some questions. What elements of connected learning and equity were achieved? Was the activity meaningful to students? Did students collaborate effectively? Were students able to meet enough curricular objectives to justify the cost in classroom time?

Speaking from the point of view of a teacher who has not formally collected data from students, there is no question that this activity is student driven, interest driven, and creates a condition of shared purpose. There is no question that students are being creative, collaborative, and communicative. Doing our work or play sessions, students are highly engaged, on-task, and enthusiastic. One satisfying moment came during our class “Final Four” when a highly athletic and competitive student, who is often not highly engaged, had just beaten a young female student, who seemed disappointed, and the young man promptly walked over to her and offered a handshake and a, “Good game!” I noticed he did the same thing with his opponent when, this time, he lost in the final.

As I was rereading excerpts from “Teaching in a Connected Learning Classroom,” and considering how our project connects to Connected Learning, the following quote made an impression on me,

“In their 2013 report, Connected Learning: An Agenda for Research and Design, Ito et al. write that connected learning is: socially embedded, interest-driven, and oriented toward educational, economic, or political opportunity. Connected learning is realized when a young person pursues a personal interest or passion with the support of friends and caring adults, and is in turn able to link this learning and interest to academic achievement, career possibilities, or civic engagement.”

I feel the bolded words strongly apply to the work in which my grade level partners and I have engaged. As a teacher, I don’t think I’ve ever attempted a learning activity that is so social. Students are now making original creations that were born from commonly shared ideas! I especially love the term “oriented toward educational opportunity” because it allows for so much freedom for teachers to be creative and use their professional judgement, while allowing students to experiment.

As I consider equity, I keep coming back to a resource identified in an earlier post, Shane Safir’s edutopia.org blog entry “Equity v. Equality: 6 Steps Toward Equity,” in which she identifies “6 ways to walk toward equity…” They are: Know every child, become a warm demander, practice lean-in assessment, flex your routines, make it safe to fail, and view culture as a resource. Additionally, in my own earlier post I said, “I can create an equitable situation if I can motivate, engage, inspire, and facilitate learning for each student, no matter their present level of development. If that can be defined as equity, sign me up!” These points remind me of a small moment I observed this week as the kids began preparing to build their prototypes. One group, which contains a student with emotional, interpersonal, and many academic needs, was working on a goal post for their paper football type game, which they were able to create. The problem they were wrestling with was how to get it to stand up on its own. This student with low confidence and limited academic success suggested sticking the bottom end of the goalpost through the bottom of a cup. It worked! His group members were able, even if briefly, to see him as an intelligent, helpful contributor. His satisfaction was easily visible.

STUDENT FEEDBACK AND WHERE WE GO FROM HERE

There are many benefits to creating a novel activity and including other educators. Normally, with a project like this, I’d initially want to keep it to myself in case it failed miserably. However, when creating a project as a result of taking a course on Connected Learning, you simply have to…connect with others! As a team, it has been interesting and helpful to be able to share our experiences and find out the subtle differences with which others have approached certain activities. I’ve marveled at their enthusiasm to tackle something new together.

One of my partners created a survey which has yielded some interesting insights. In my career, there are not many lessons that have ended with students saying things like,

- “I enjoy creating things with others.”

- “I think this project offers collaboration and creativity.”

- “It helps students be able to challenge themselves in a fun way.”

- “The students are more engaged in the work and are still having fun.”

- “It gives you the opportunity to work with other people.”

- “You can learn about teamwork and learn how to become more creative.”

Most of the student comments focus on collaboration, which has caused me to ask the question: Is an activity rigorous enough if facilitating successful collaboration is the greatest outcome? When one considers that this project does that, plus some math, writing, and oral communication practice, I have a hard time saying, “No.” Additionally, isn’t collaboration considered a 21st century skill?

Currently, students are working diligently, with near 100% engagement, on their prototypes. Soon, student groups will introduce their game creations to the class, allow others to play, get feedback, analyze, and create final, aesthetically pleasing versions. Eventually, our three classes will mix so that every student in the grade level will have access to everyone else’s creations. This “Arcade Day” will allow students to approach each new game as a kind of expert, since they will have done so much work perfecting their own games. We will discuss how their own experience as game makers impacts the way they look at the arcade games of others. Additionally, students will complete in persuasive essays associated with game playing/making.